As a disability artist, researcher and creator, OCAD University Assistant Professor Dr. Pam Patterson explores issues around boundaries, borders, edges, and how she might perceive these and transform/transpose them using photography, video and performance.

She is the acting leader of the Creative Research Inclusive Practices (CRIP) Lab and director of the 113Research Projects Gallery. She has been working as a cultural producer and educator in the arts and education for over 50 years in various settings and institutions. These have included The Stratford Festival Theatre, The Banff Centre, the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education and more.

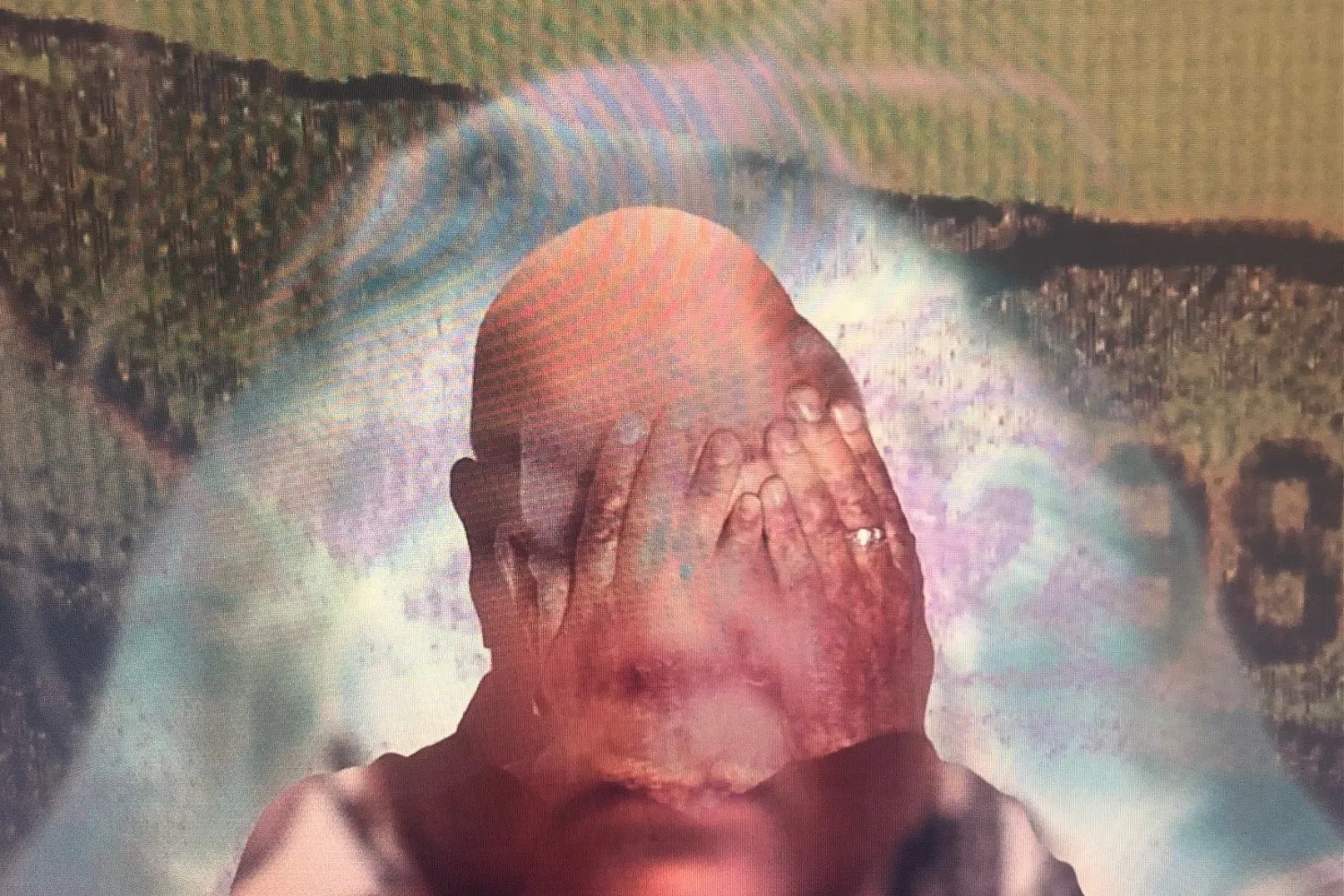

Dr. Patterson’s most recent series, Ocular Occurrences at 113 Research Projects Gallery, opens on Sept. 19 at Tangled Arts + Disability. This exhibition explores tensions between visual distortion as generative and desirable, and the medical mapping that seeks to contain and define such distortion. She asks, “What can a body do? What can a body do to?”

On Sept. 27, Dr. Patterson is speaking as part of the National accessArts Centre’s Won Lee Artists and Community Talks Series. The online session, Care Mad/CRIPping as Cultural Practice: A Provocation, is facilitated by Bushra Junaid and hosted by artist and scholar Ana Moyer with multi-media artist and writer Karen Augustine.

Dr. Patterson, tell us more about your current research.

My current work has been joyfully investigating “hacking” strategies that disability creatives use to access institutions, challenge and change policies and practices, and generate complexity in their cultural work.

Disability aesthetics, as theory, and the work by disability creatives provides, for me, an ever-evolving model that envisions a much more inclusive and stimulating social and cultural landscape.

What drew you into this field of study in the first place? Was there a turning point or defining moment?

Disability as focus has always lurked in my background: my brother, born developmentally delayed, was often confused by, and hidden away from, others.

As a single parent, I feared being unable to support my child with cognitive/learning disabilities, so I closeted my own disabilities as best I could for decades. As a result, this has meant that I have often had to deal with self-loathing, physical pain and emotional frustration.

These experiences not only fueled my creative work as a dancer, actor, mime, performance and visual artist, and teacher but also gave me a way to generate complex strategies for explicating, accessing, and using disability experiences as potentialities for action.

What problem or question is your research trying to solve or answer?

My current work revisits the potential promises I felt as a graduate student in the 1990s. Generative – and modernist-shattering – possibilities emerged from my study in such fields as feminist post-structuralism, critical pedagogy, critical race theory and postmodernism. Postmodernism, especially embodied for me a kind of deliberate ambivalence which unfixed, multiplied, and unsettled many of my assumptions or preconceptions around self, people, culture, and place.

What has been bubbling up for me lately as a result of this past remembrance has been around this idea of “deliberate ambivalence.” My interest is specifically in how oscillation, active within a space of ambivalence, might create complexity in a (still) polarized world.

I ask, “Can making a deliberate choice to investigate – however uncomfortably – the (generative) space found amongst often problematic conflicting and binary concepts such as between a “disabling body” and a “disabling society” or between “mainstream art” and “disability art” be productive?

Canadian disability scholar Elisa Chandler speaks to the inequities that disability arts community members have faced. Assumptions by some in the mainstream might allude to disability artists as being unskilled, unprofessional, and lacking artistic and political insights. Such attitudes only serve to push disability art to the “outside” creating a bifurcation between “legitimate” art/artists and disability art/artists.

How do you see your research contributing to your field or affecting people’s lives in the real world?

The work some of my disability students at OCAD U are now taking up to explore disability aesthetics and community access practices is contributing to more intricate and less predictable cultural perceptions, processes and forms.

I am now seeing, thanks to their and my collaborative work, shifts in curation and exhibition practices, and in the ways other fields such as fashion, landscape design and architecture practice.

There are some wonderfully quirky, fun, and creative objects, designs and environments emerging as our artists and designers become more comfortable with these ideas and processes. There are more opportunities for people to see, and publicly – and joyfully – engage with exciting and complex bodies and forms.

Are you working with any collaborators, institutions, or funding bodies on this project?

As acting leader of the Creative Research Inclusive Practices (CRIP) Lab at OCAD U, I have been very fortunate to have access to many disability research creatives here in Toronto, across Canada and internationally. Every two months we meet and share research initiatives and support graduate student work.

I've received generous funding for my projects from arts councils at the municipal, provincial, and national levels, from the Jackman Humanities Institute’s Fellowship for the Arts, Cultural Pluralism and the Arts, and have received some Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) seed funding from OCAD U and University of Manitoba (thanks to my ofttimes research partner Dr. Joanna Black).

I'm currently working with some generous people/institutions right now: Jack Hawk (curator) and Sean Lee (programming director) at Tangled Arts + Disability around my upcoming solo vitrine exhibit, Ocular Occurrences: Sites of Perception and Bushra Junaid, project consultant, Won Lee Arts Hub/National accessArts Centre contributing to the Won Lee Artists and Community Talk Series (Sept. 27 on Zoom) around disability communities of/in care.

What do you hope people – both inside and outside of your field – take away from your research?

In taking up deliberate ambivalence as a working metaphor/methodology for the making, viewing and reading of “disability” cultural work, I hope to energize and sustain my own work as an artist and academic and likewise encourage student investigations.

Positioning my practice as teacher and academic this way also serves to focus study on the transitional and unfixed nature of work with/in disability culture.

One of my favorite quotes from disability aesthetics theorist Tobin Siebers is, “One of the oddities revealed by a disability studies perspective on aesthetics ... is how truly unreal and imaginary are nondisabled conceptions of the human body.”

Ambivalence is often understood as having negative connotations, as does disability. But if we deliberately position our cultural study and teaching in an ambivalent space as generative, we can then embrace the potency of disability for shifting and expanding our preconceptions of culture.