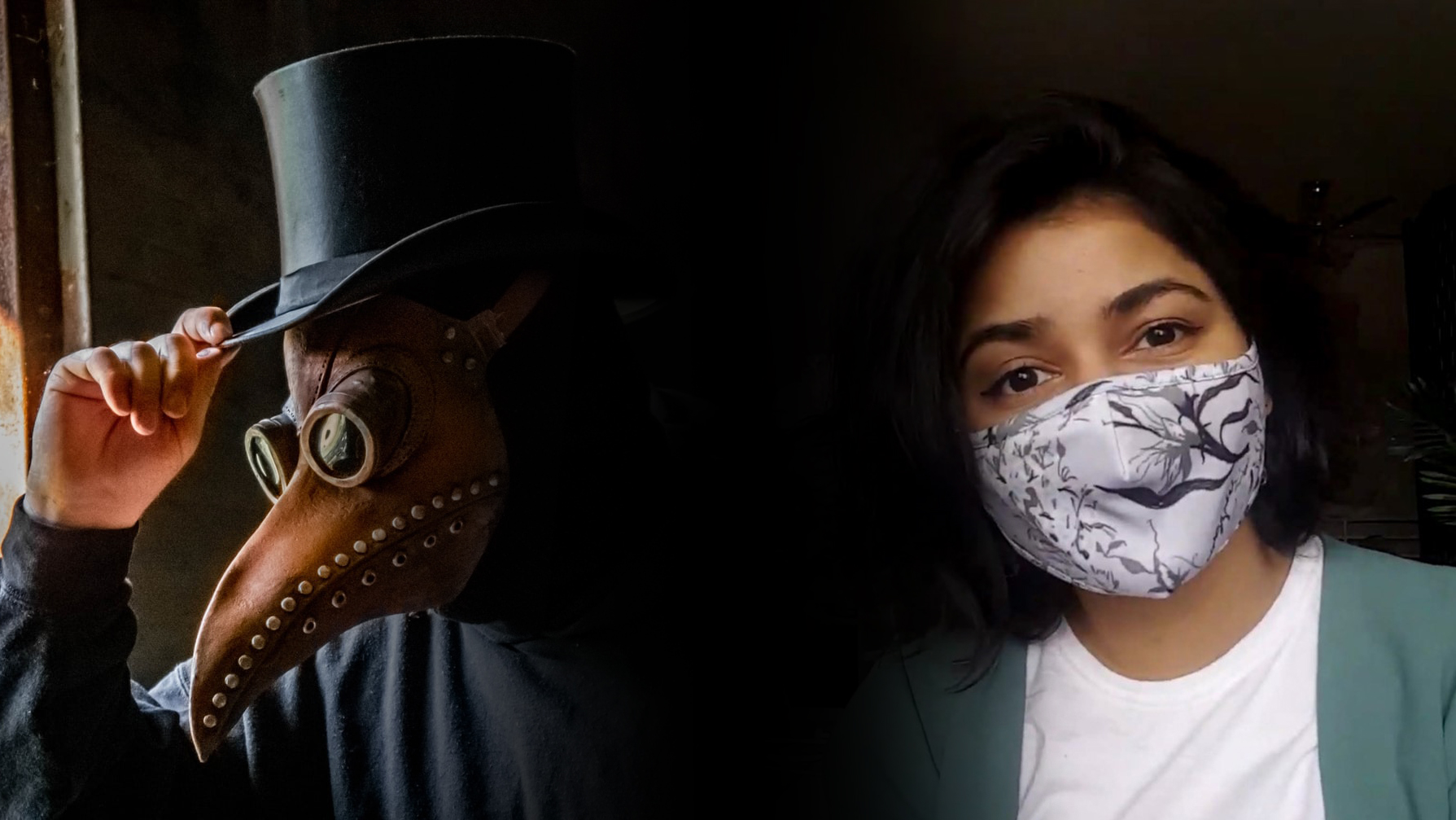

Right: Mask created by Apoorva Varma (2017 MAAD grad) textile print design titled Lady of the Night (2020). The mask was created in collaboration with Le Galeriste. Photo by Apoorva Varma.

Throughout human history and across different cultures, masks have taken on diverse forms and functions, from costume accessory, to spiritual accoutrement, to safety gear, to fashion apparel.

The COVID-19 pandemic, however, has introduced a dynamic new chapter in humanity’s multi-millennia old relationship with face masks.

“There are many uses and purposes for making and wearing masks,” says Nithikul Nimkulrat, acting chair, Material Art & Design program, OCAD University and a textile practitioner-researcher. Their meaning has changed slightly during the pandemic.”

A mask for every occasion

Encyclopedia Britannica notes that historically, some peoples in Africa, East Asia and Oceania wore masks for religious and social ceremonies pertaining to fertility rites, weddings, funerary customs or protection against disease. Mask wearing also featured prominently in folk celebrations in Europe, shamanistic ceremonies in Korea, and harvest blessings by Indigenous peoples.

In military contexts, ancient Greek and Roman warriors and Japanese samurai donned grotesque masks to intimidate their enemies. Masks have also been worn as costumes in the performing arts—in the courts of ancient Middle Eastern Kings, the masquerade balls of Shakespeare’s works, and the spicy scenes of “Eyes Wide Shut.” Today, we wear them at street festivals—Mardi Gras in New Orleans, the Day of the Dead in Mexico, Carnival in Brazil—and for holiday celebrations such as Halloween and Purim.

The wide range of purposes for masks is matched by the plurality of their materials, which have included wood, metals, shells, fibres, ivory, clay, horn, stone, feathers, leather, fur, paper cloth and even corn husks.

Masking for safety

Well before the COVID-19 pandemic gripped the globe, wearing a surgical mask for safety—one’s own and that of others in society—has long been a cultural norm and common hygiene practice in many parts of Asia.

“In countries like China and Japan, when people get sick, it’s common for them to wear masks, because they don’t want to infect others. People are more considerate of others,” Nimkulrat, says.

The onset of the 1918 influenza epidemic led many cities worldwide to introduce mandatory masking orders. In Japan, complying with this order was viewed as an act of modernity and national obligation; in Canada and the U.S., some viewed compulsory mask wearing as infringing on their civil liberties.

Masking for style

At the start of the coronavirus pandemic, we mainly turned to standard surgical/medical masks to protect ourselves against catching and spreading the virus. They are designed to tightly fit the face and filter out large air particles.

But before long, more stylish options emerged that quickly became popular, even though they may not offer the same level of protection. Nimkulrat notes function is being superseded by other concerns.

“Once we had to wear masks regularly, we got bored of the basic option…People need more pleasure in their lives, so they go for more stylish masks, or designs that project a desired social status,” says Nimkulrat, noting that this trend has been amplified by media coverage of celebrity mask choices and the rise of mask chain jewelry.

Multi-meaning masks

In some parts of the world, masks have become political as some people use them to make statements about their views, or reject wearing them altogether in protest of “government overreach” or due to a distrust of science.

At the same time, we have seen innovations in face coverings that address the needs of people with disabilities, such as the government of Thailand introducing versions with see-through mouth areas that enable deaf people to communicate.

Nimkulrat also observes how the ubiquity of masks today weakens criticisms of face coverings worn for religious purposes.

If it’s OK to wear a mask to protect ourselves against a contagious disease, it makes us rethink why it’s not OK to do so for religious beliefs,” she says. “Masks may have helped take away the stigma.”